Music + Arts · February 10, 2020

Two Roads to Calvary

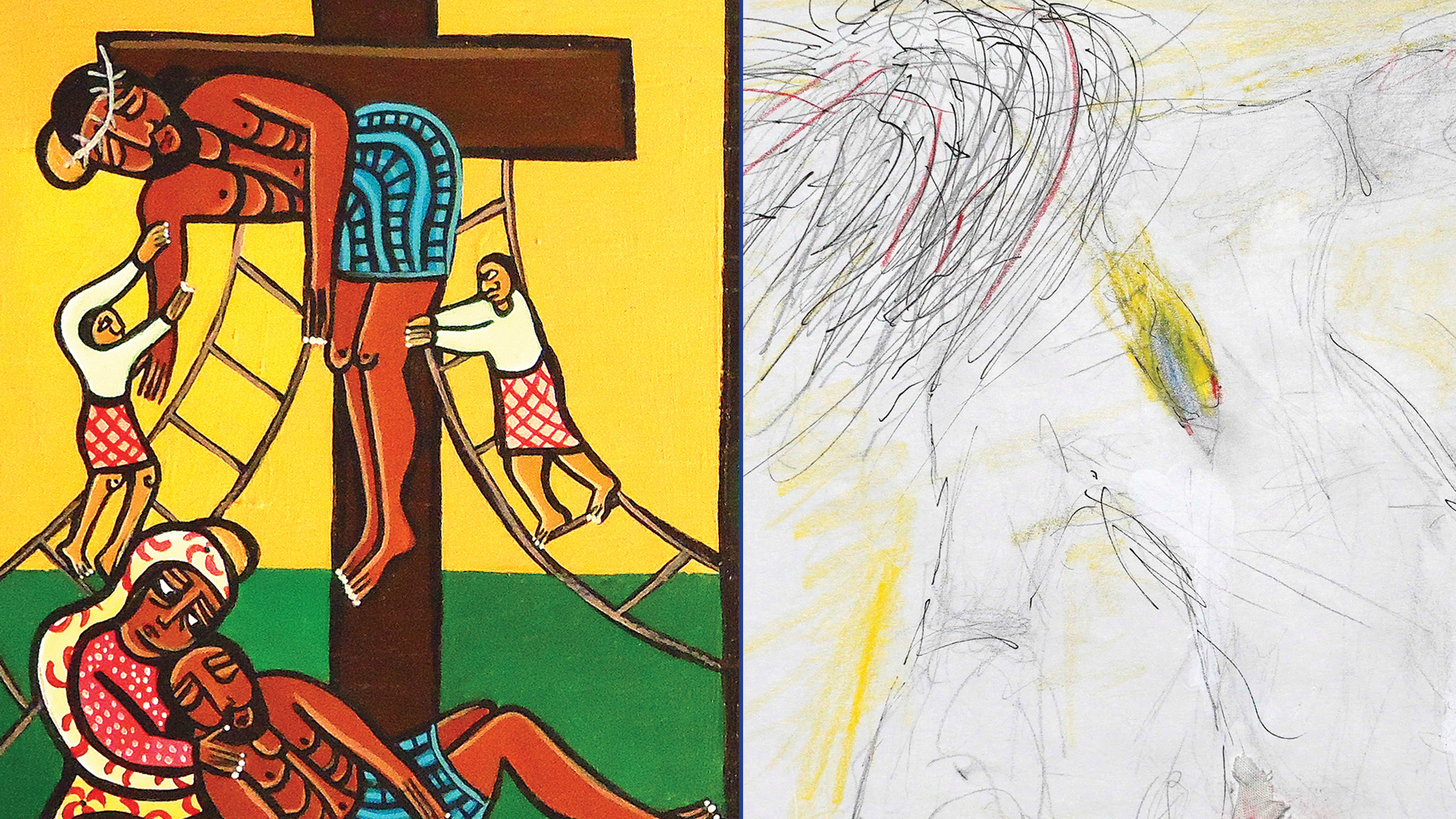

This unique, dual exhibition features the Stations of the Cross as depicted by two contemporary New York artists—both named Laura.

Presbyterian churches are not known for displaying the Stations of the Cross—much less including them in their Lenten liturgies. This Lent, we plan to change that. Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church marks the return of this 15th-century Christian tradition with a display of two artists’ interpretations of the Stations, and an evening of devotion.

On Sunday, Feb. 23, the Arts & Our Faith Committee presents Two Roads to Calvary, an exhibition featuring two New York artists who are well known to the congregation—Laura Fissinger and Laura James. And on Tuesday, March 17, we invite you to learn and practice the Stations as a devotional exercise. This workshop—led by Seamus Campbell, director of Outreach Ministries and an Old Catholic priest—is part of our series of classes on Lenten spiritual practices.

Fissinger’s Stations were commissioned by the church to add to our sacred art collection. James’ were created as part of a humanitarian effort to restore earthquake-damaged churches in Haiti. Although their subject matter was the same, the artists traveled two distinct paths in depicting Christ’s walk to Calvary. We invite you to read their stories.

Laura Fissinger: 'The Light Wins the War'

Laura Fissinger’s Stations of the Cross are unlike any you have ever seen. Most noticeably, none of the other people are there. The nails are there, but the executioners are not. The lifeless body comes down from the cross, but we don’t see the grieving mother and her tender arms holding her son.

“We know from the stories that they are there,” Fissinger explains. “But on some visceral level, to me, Jesus was utterly alone in that journey.”

The fully human Jesus—in his fear, vulnerability and pain—is the sole focus of Fissinger’s stark panels. This decision on the artist’s part led her to reduce her Stations from 14 panels to 12, eliminating Simon of Cyrene (who helped to carry the cross) and Jesus’ encounter with the women of Jerusalem.

“My depiction of Jesus is based in the Garden of Gethsemane,” Fissinger says. “I felt like I saw the human part of Jesus reaching for his friends in agonizing hours, sweating blood. And they were unable to be there for him when he felt so alone. That’s the Jesus I found myself drawing.”

Fissinger’s Stations are raw and largely abstract. Her Jesus has no face, his agony expressed in wild strands of hair, the contortions of his body, and patches of white linen stained with dirt and blood. The images would be monochromatic were it not for a persistent yellow, blue and purple flame.

It is that flame, not a face, that we see on Veronica’s veil. “Even on that panel I wouldn’t try to draw what Jesus looks like physically, because nobody knows,” she says. “The flame of his divinity seemed true in a spiritual sense.”

Fissinger’s hope is that viewers will feel connected to the Jesus in her Stations. To experience empathy with him, she believes that people need to see themselves in him.

“I have always thought that God was quite deliberate in putting himself in the person of his son on earth before there was photography and a lot of representational art,” she says. “God did not want to have himself in our form be ‘other’ for anyone. We know Jesus was male, but I believe that his essential self was not constrained by race or gender or age or anything else. We are all included in him.”

Fissinger has dealt with clinical depression and generalized anxiety disorder since she was very young. This background, coupled with a fire-and-brimstone, heavy-on-the-guilt Catholic childhood, initially made the Stations “torturous for me.” She spent more than a year completing the project.

“I prayed and prayed until I found the emotional energy,” she recalls. “I just kept feeling God saying ‘One more step, keep going.’”

The Stations helped Fissinger in her long-sustained effort to make peace with her religious past. The two largest images in her series are Jesus’ death on the cross and Jesus laid in the tomb. In these panels, the physical body is gone, leaving only the divine flame.

“There is the miracle, the releasing of our sin burden, our release from the bond of evil, the light winning the war,” she says. “The dark may win many battles, but the light wins the war.”

Laura James: 'A Reflection of the Creator'

In January 2010, a massive earthquake in Haiti killed an estimated 160,000 people, and damaged or destroyed nearly 300,000 homes and public buildings. In New York, a nonprofit organization, From Here to Haiti, was established to help the nation rebuild.

Laura James found a role for art in healing Haiti.

James, a Bronx-based artist, has had a longtime association with the Archdiocese of New York’s Office for Black Ministry. Friends there connected her with From Here to Haiti and the work they are doing to restore churches. Patricia Brintle, president of the organization, recognized how James could contribute to the restoration of the Parish of St. Jean Baptiste in Sassier, a remote village in southwestern Haiti.

The parish serves a rural populace of 10,000 spread over 30 square miles. It is an area with few paved roads, sewers, electricity or other public services.

“Laura came up with the idea of bringing the painted Stations of the Cross to Haiti,” Brintle says. “I thought it would be a great opportunity to bring sacred art that is culturally appropriate to the parish.”

“Culturally appropriate” are keywords for James. Born to devout Antiguan parents, James and her sister spent a lot of time in church, where she learned the stories of the faith from an Illustrated Children’s Bible. She remembers the racial bias in those illustrations.

“More often than not, Christian art has been depicted from a Eurocentric point of view, and so excludes other ethnic groups from seeing themselves as a reflection of the Creator,” she says. “In areas affected by poverty, where life is typically more physically and economically challenging, the need for spiritual elevation is important. Our goal is to offer parish members artwork that is more authentic and reflective of their community’s valuable heritage.”

James’ Jesus is black-haired and brown-skinned, enveloped in the vibrant color of traditional African art. There is a fluidity to her human figures, each with dark, piercing eyes. It is a signature style that James has developed over more than two decades.

James was just 19 when she discovered Jacques Mercier’s Ethiopian Magic Scrolls, a 1979 text that documented an ancient form of indigenous art that drew from Christian and Muslim traditions. She began modeling her work after images that date from the fourth century.

Two examples of her work are on permanent view at Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church. Sermon on the Mount, commissioned by the church in 2016, hangs in

Kirkland Chapel. And Creation, a gift of member Sheila Greene, is just outside the Chapel, above the stairway leading to the Christian Education Center.

As James developed her craft, she found an eager market among publishers looking for multicultural depictions of sacred stories. “I was lucky to sell my work very early on,” she says, “to have a style that met a need for non-traditional religious images. But the art came first.”

After James’ Stations of the Cross depart Fifth Avenue, she hopes to accompany them to their next and final stop—Sassier.